The 2×2 matrix that shapes restaurant tech GTM

Most GTM problems in restaurant tech aren’t due to bad reps or weak product.

They come down to one thing: misalignment between how you sell and how restaurants buy.

This is part one of a 3-part series on restaurant tech GTM clarity starting with the quadrant most vendors ignore: the one they’re standing in.

We’ve talked before about mandate leverage, the idea that some vendors can sell top-down to corporate (and enforce usage), while others are forced to win hearts and minds one location at a time. That concept was the basis of There are only 2 GTM strategies for restaurant tech companies.

But pricing model matters just as much. We explored this in The restaurant industry’s SaaS pricing paradox, where flat-fee SaaS often struggles to balance margin pressure with rep quotas, especially in markets where volume-based monetization wins.

The GTM matrix

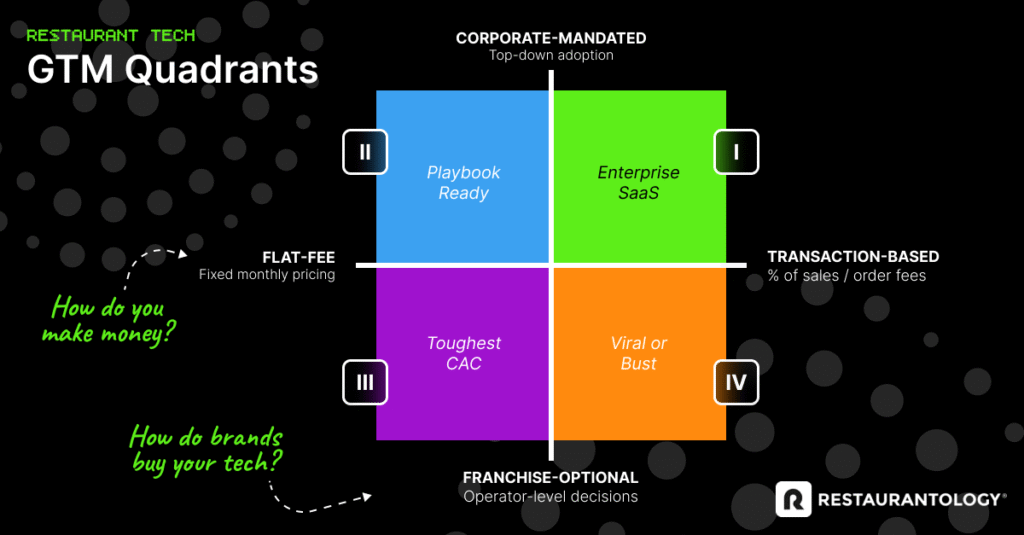

Stack those two ideas together, and you get a clear 2×2 GTM matrix:

X-axis: Pricing Model (Flat-Fee Software ←→ Transaction-Based)

Y-axis: Mandate Leverage (Corporate-Mandated ←→ Franchise-Optional)

The quadrants

The result is four distinct GTM quadrants, each with distinct risks, growth patterns, and constraints.

Quadrant I: Enterprise SaaS (Transaction-Based + Corporate-Mandated)

This is the modern sweet spot for scale. Monetization grows with usage, which makes even low-AUV or small-unit brands viable. Rollout is enforced from the top. As long as the underlying transaction volume stays healthy, revenue scales with the brand. Think point-of-sale, payment processors, marketplace-style ordering (like ezCater), or reservation platforms with per-cover pricing. Corporate mandate protects volume. Volume protects margin. CAC is low, expansion is natural, and revenue is recurring by default.

Quadrant II: Playbook Ready (Flat-Fee + Corporate-Mandated)

This is the classic SaaS motion—high-margin, top-down, repeatable. CAC efficiency is strong, implementation is predictable, and expansion can be layered in over time. Most enterprise-facing tools with compliance pressure (e.g. workforce management, security, loyalty) aim to live here. The challenge isn’t adoption, it’s ongoing value: your product has to keep justifying its line item post-rollout or risk being replaced.

Quadrant III: Toughest CAC (Flat-Fee + Franchise-Optional)

This is hard mode. You’re charging a fixed monthly fee, but adoption is entirely up to the operator. Every sale is uphill. CAC balloons fast. Companies in this quadrant often overhire before their lead gen is ready or pricing is market-approved. Reps need to be surgical or the math breaks. This is where many ops platforms, marketing tools, and even AI systems live if they haven’t secured preferred vendor status or deep channel partnerships.

Quadrant IV: Viral or Bust (Transaction-Based + Franchise-Optional)

This is where most GTM friction lives. No mandate, no margin buffer, and you’re betting on usage-based revenue one unit at a time. To work here, your product has to earn its keep by either driving top-line revenue or embedding itself inside a larger workflow. Think QR-pay tools, last-mile delivery layers, or lightweight integrations that sit on top of existing POS. GTM here often depends on virality, value, or being bundled into someone else’s install base.

Of course, your quadrant is only half the story. Even with a strong GTM motion, success depends on how your target brands are structured… and who gets to say yes.

The industry picks your quadrant more than you do

Most vendors don’t get to choose their quadrant outright. The restaurant industry has entrenched expectations—about both pricing and decision rights—that shape where you land.

On the pricing front, operators love the psychological safety of usage-based fees: “If I don’t use it, I don’t pay for it.” That’s why a single-unit food truck with crazy volume can end up paying more than a 10-unit chain running a flat $100/month SaaS.

And on the mandate side, franchised brands rarely allow full-stack control. Even with corporate enthusiasm, rollout often hits a wall of uncontactable operators, independent LLCs, or loosely enforced tech standards. Unless you’re in the Franchise Disclosure Document (FDD)—or part of a negotiated vendor list—you’re likely flying blind.

Some vendors bridge quadrants, or shift over time

Toast is a good example of bridging quadrants. Technically, it’s flat-fee software. But because Toast is also the payment processor, they earn transaction fees on every sale. That lets them subsidize the SaaS to lock in long-term margin. It’s why you’ll sometimes see Toast deployed like a Quadrant I player, even though their price tag says Quadrant II.

Olo is a clear example of shifting over time. They started in Quadrant II (flat-fee, corporate-mandated) and dominated in enterprise early on. But with Olo Pay and Rails, they’ve added transaction-based monetization, moving toward Quadrant I. That shift lets them grow revenue per location without raising SaaS prices.

Others make the reverse move, starting in Quadrant IV and working their way toward Quadrant II by introducing a flat-fee tier, bundling value, or getting listed as a preferred vendor.

Use the matrix to audit your GTM reality

Most early-stage restaurant tech companies aren’t honest about which quadrant they’re actually in. They staff like there’s unlimited TAM, price like they’ve never seen a restaurant P&L, and outreach like mandates don’t matter.

But pricing power is shaped by the category you’re in. Mandate leverage depends on what you’re selling and which brands you’re targeting. Neither is fully in your control.

This matrix won’t solve every GTM problem, but it will clarify your constraint:

- If you’re flat-fee and non-mandated, efficiency is everything.

- If you’re transaction-based and mandated, the sky’s the limit.

- If you’re neither, you need a wedge like viral utility, embedded adoption, or partner distribution.

Before you scale your team, change your pricing, or reposition your product, figure out which GTM quadrant you’re in. From there it should be pretty easy to assess if your GTM strategy matches reality.

In Part 2, we’ll explore the other side of the equation: how restaurant brands are structured, and what that means for your sales motion.