Segment-based POS adoption: how brand size shapes tech stack

Why does Toast show up in so many 10-unit to 20-unit restaurant groups, yet far less often in 500-unit enterprises? Why does Aloha remain the default for many legacy chains, yet rarely appear in newer, smaller regional concepts?

These are not questions of brand preference or software features alone. Restaurant POS adoption follows a pattern because the economics of operating a restaurant change as a company scales. Brand size, meaning the number of units in a restaurant group, influences how a POS is evaluated, how it is paid for, how quickly it can be deployed, and how risky it is to replace.

What follows are data-backed observations on how market structure, cost models, payment economics, and operational friction shape which POS systems succeed across different segments of the industry.

Brand size changes what a POS decision actually is

A 10-unit restaurant group and a 500-unit enterprise are not solving the same problem when they choose a POS.

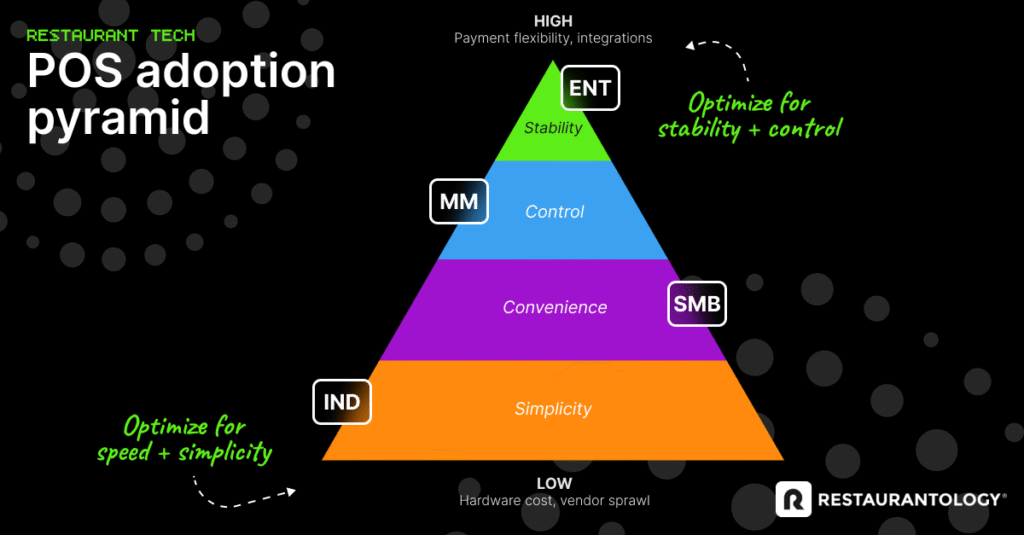

Smaller groups tend to prioritize speed, affordability, and bundled simplicity. They often want one vendor to handle POS, online ordering, email marketing, gift cards, and credit card processing. They do not want to source five different vendors and connect them through APIs.

Mid-market restaurant groups deal with added complexity. They may need franchisor controls, deeper reporting, payroll integrations, delivery channel data, or multi-brand menu management. In this segment, the POS decision becomes less about convenience and more about control.

At enterprise scale, POS becomes infrastructure. These companies often sign multi-year contracts. They negotiate credit card processing rates separately. They plug POS into custom reporting systems, labor platforms, inventory models, and loyalty vendors. Replacing a POS is closer to a capital project than a software upgrade. It can require new hardware, new payment routing, and retraining across hundreds or thousands of employees.

Because the cost of disruption grows as brands scale, larger restaurant groups avoid switching unless the benefits are overwhelming. This is why enterprise POS migration happens slowly. Not because the software is inherently better or worse, but because the organizational risk is higher.

Vendors evolved to match the market dynamics of each segment

Over the last two decades, that reality has shaped the POS market into clear segments. Some platforms were built for small, fast-moving operators and became the default for emerging brands. Others were designed for scale, control, and custom integrations, and became embedded in legacy enterprise chains.

Toast, Square, and SpotOn grew in the independent and small-chain segment because those operators valued speed, bundled payments, and low upfront cost. Aloha, Micros, and Brink became fixtures in enterprise because they allowed flexible payment processing, deeper integration, and long-term stability.

Once a POS system becomes dominant in a segment, its entire business model tends to form around that segment. Which leads to the next question: what happens when a vendor tries to sell into a market it was not originally built for?

Moving upmarket is hard, even for SMB-born POS providers

Toast and Square grew by making POS feel like software instead of infrastructure. They could be deployed quickly, often on tablets a restaurant already owned. They bundled payments, online ordering, email marketing, gift cards, payroll, and more into one platform. Adoption was simple, especially compared to legacy POS systems that required heavy hardware installs and on-site technicians.

This model, fast to deploy and cost-accessible, worked well across the long tail of the industry. But as these cloud-native systems began targeting 50-unit, 100-unit, or 300-unit brands, they ran into a different economic reality.

For most modern POS platforms, the real revenue engine isn’t subscriptions, but credit card processing fees. Smaller operators accept that trade-off. They get an all-in-one platform with minimal setup, and in return, they pay higher payment processing rates.

Enterprise brands do not operate this way. They process millions of annual transactions and negotiate their own merchant processing rates to protect margin. So when a vendor like Toast tries to win a 300-unit or 500-unit chain, it faces a fundamental choice: require the restaurant to use Toast’s payment rails, discount processing fees to match enterprise-negotiated rates, or allow external processors and sacrifice core revenue.

None of these options are painless. That is why enterprise deals for SMB-born vendors often involve concessions. These wins are pursued for strategic reasons like brand credibility and case studies, not immediate profitability.

At the enterprise level, winning deals is no longer just about software features. Most core functionality is now commoditized. The harder question is whether a vendor can adjust its business model to match enterprise economics without compromising the foundation that made it successful in the first place.

Moving downmarket is just as hard for legacy enterprise systems

If Toast struggles to move upmarket, why do Aloha, Micros, Brink, or other enterprise systems not simply move downmarket and compete in the independent space?

For NCR, Oracle, and PAR, the answer is straightforward: cost, both to sell and to support.

Selling to a 5-unit restaurant group is expensive when your company was built to win enterprise-level contracts. Finding and targeting smaller operators often requires local field reps, trade shows, or in-person demos. Those reps are expensive, and so is the follow-through.

And if you do win the deal, the costs keep stacking. Hardware installation, network configuration, menu programming, training, and on-site support all require people. Then come the support tickets, billing adjustments, outages, retraining after staff turnover, and CRM updates with every activation, cancellation, or ownership change. None of this scales well when your revenue comes only from a license fee.

If a customer pays only a software subscription and does not route card processing through the POS vendor, the economics simply fall apart. It’s difficult to profit from very small brands when your operating model was built around long-term contracts and enterprise support teams.

There is a possible solution here, and most enterprise-born vendors have tried it in some form: create, acquire, or rebrand a lighter, more modular POS offering. Shift4 continues to acquire smaller platforms, some cloud-native and others legacy hardware-based, and present them as an on-ramp for new customers. The theory is sound. Lead with something simpler and cheaper, then graduate the customer into the full platform as they grow.

The challenge is timing. The market already rewarded newer vendors for solving the lightweight problem more than a decade ago. The segment that values fast deployment and bundled simplicity is now accustomed to Toast, Square, and SpotOn, and switching costs are low only when the first system is chosen, not when a replacement is being evaluated.

Rather than chase a segment where customer acquisition is expensive and churn is high, Aloha, Micros, and Brink continue to focus on brands that value depth, stability, and payment-processing autonomy. Their weakness is cost to scale down.

The main factor stalling a POS change: migration friction

Even when a brand wants to switch, the cost and speed of deployment determine whether the change happens.

Most modern POS platforms are software driven. They run on tablets or lightweight terminals, and additional modules can be activated inside the platform. A small team can go live in days or weeks.

Aloha and Micros were built in a different era. A full-service restaurant might use several terminals, kitchen display screens, printers, and an on-site server. Installing or replacing this hardware can cost tens of thousands of dollars per location. Replacing a system like this means new hardware, installation work, and staff retraining. It’s a disruption, not a toggle.

That creates a psychological barrier as much as a financial one. When a restaurant already has 80 to 90 percent of what it needs from its current POS, the motivation to switch must be overwhelming. Buyers evaluate migration effort, not feature lists. They want more capability for less money, because otherwise the change feels irrational.

Once a category reaches maturity, the question shifts from “Which system is better?” to “Is the pain of switching worth it?”

This is why vendors seize on rare moments when the status quo is disrupted, such as outages or contract renewals. Those moments create urgency. Outside of them, the default state is inertia.

Migration friction, more than preference, is what keeps the POS market segmented.

Vendors do not pick segments. Segments pick vendors.

Toast did not simply choose the 10-unit to 50-unit market. That segment rewarded what Toast offered: fast deployment, integrated payments, and bundled functionality.

Aloha did not avoid smaller operators. The enterprise segment rewarded stability, payment-routing flexibility, and the ability to integrate with best-in-breed partners.

These companies built products the market would pay for. As the market shifted, they adapted. Toast now pursues mid-market and enterprise wins because growth demands it. Aloha has introduced more cloud-based tools because some customers want them. But neither can escape the economics of the segments they were built to serve.

The restaurant industry amplifies these dynamics. Margins are tight, labor turnover is constant, service expectations are high, and revenue is influenced by external factors. Any technology that risks downtime, retraining, or operational complexity gets evaluated through the lens of fragility, not possibility. That shapes everything from integration priorities to pricing models to which vendors are considered strategic or replaceable.

Understanding POS segmentation helps explain not just where vendors win, but how the broader restaurant tech ecosystem evolves around those wins.

Why this matters

If you only look at features, the POS market can appear chaotic. But once you layer in brand size, economics, and operational constraints, the patterns become clear.

Smaller brands choose speed and simplicity because they have limited IT resources and need to move quickly. Enterprise brands choose stability and control because disruption is expensive at scale. Vendors position themselves where their business model is rewarded.

This is why knowing a restaurant’s POS is so revealing. A brand’s POS often reflects how it makes decisions, how it manages financial risk, and how it approaches technology adoption. It signals whether speed matters more than control, whether payments drive margin strategy, and how much organizational friction the brand is willing to tolerate.

Movement does happen. Toast is showing up more often in 50-unit and 100-unit brands than it did two years ago. Certain legacy systems are being replaced more quickly than before. But these shifts happen within economic structure, not outside of it.

A restaurant’s POS tells you how the business runs. It reflects how they weigh control against speed, how they manage margin against convenience, and how much operational friction they are willing to tolerate. Learn the POS, and you understand the operator.